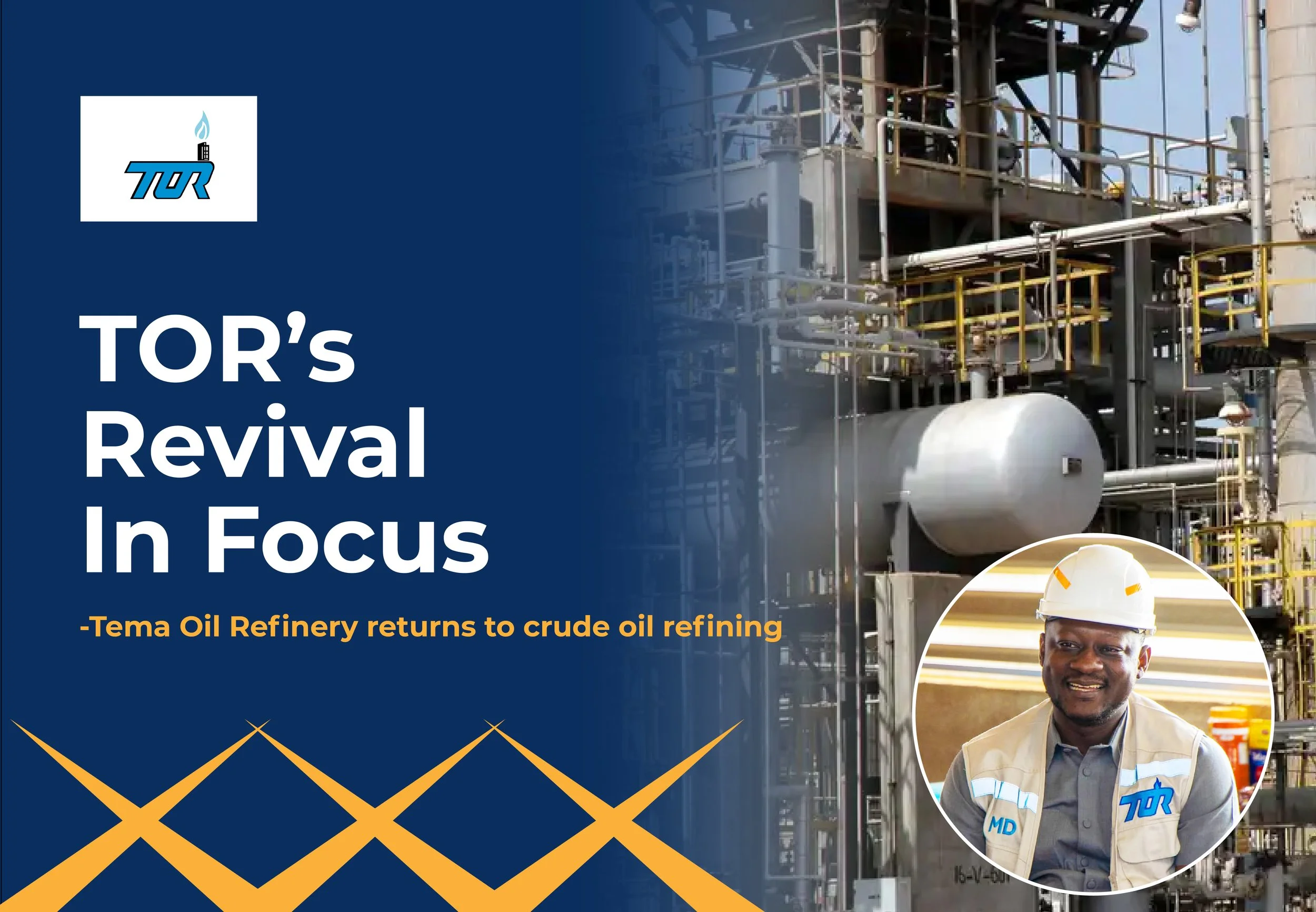

Downstream Sovereignty and 1,144 Direct Jobs Secured: TOR’s Revival in Focus

Not long ago, TOR was defined by demonstrations, missing crude, and chronic idling. Its revival now tells a different story. With workers back on active duty and expansion plans signalling further labour demand, the refinery is shifting from a governance problem to an employment anchor in Ghana’s evolving energy architecture.

Tema, Ghana | February 5, 2026 - For much of the last decade, the Tema Oil Refinery stood as a monument to unrealised industrial promise. Vast steel assets lay largely dormant, while its workforce oscillated between anxiety and agitation. Demonstrations over idling capacity, allegations of mismanagement, missing crude condensate, and open confrontations between labour and management became part of the refinery’s public identity. TOR was no longer discussed as a jobs anchor or a strategic asset, but as a liability the state struggled to explain.

That narrative is now being deliberately dismantled.

At the centre of TOR’s revival is a development often underplayed in macro energy debates but deeply consequential in political economy terms: jobs. Not prospective employment, not abstract multipliers, but tangible re-engagement of skilled labour across refining, maintenance, logistics, safety, and auxiliary services.

According to the Managing Director of TOR, Edmund Kombat Esq.,: “The revival of TOR has directly safeguarded 1,144 jobs and continues to create opportunities for the nation’s teeming youth, particularly young engineers.”

In recent public remarks on the international stage, Ghana’s leadership has pointedly framed TOR’s return not merely as an energy story, but as an employment and sovereignty one. The subtext is unmistakable. Refining capacity is not just about molecules; it is about livelihoods, institutional confidence, and national self-respect.

From Protest Lines to Production Lines

The contrast with TOR’s recent past is stark. In April 2023, workers threatened demonstrations over what they described as prolonged idling and administrative failure. Media reports chronicled warnings against “illegal strikes,” even as questions mounted over missing crude condensate valued in the millions of dollars. These were not isolated incidents but symptoms of a refinery trapped in governance paralysis. Skilled technicians watched their competencies atrophy while the facility they trained to operate became increasingly inert.

That period now functions as a baseline against which current developments are being measured.

Under the ongoing reset, TOR’s workforce is no longer positioned as a cost centre to be managed down, but as a strategic input to be reactivated. The refinery’s restart has pulled engineers, technicians, safety officers, and support staff back into active operational roles, while catalysing indirect employment across haulage, storage, port services, and compliance functions. In policy terms, this is industrial labour reclamation, not cosmetic rehiring.

Jobs as Energy Sovereignty in Practice

Energy sovereignty is often framed in barrels, megawatts, or balance-of-payments arithmetic. TOR’s revival adds a more grounded dimension. A functioning refinery internalises value that would otherwise be exported alongside crude, a fact emphasized by the President of Ghana in the course of his latest international engagement. It keeps technical skills within national borders and preserves institutional memory that cannot be repurchased on the spot market.

The regulator has been explicit on this point. The National Petroleum Authority has described TOR’s return as the reclamation of Ghana’s refining backbone, a phrase that carries both technical and labour implications. A backbone supports weight. In this case, it supports jobs, pricing discipline, and downstream resilience.

Sector ministry and presidential engagement have followed a similar script. Public endorsements from downstream industry players have framed TOR not as a sunk asset being reluctantly revived, but as a platform for inclusive industrial participation. This matters. In a country where energy infrastructure has too often been discussed in fiscal abstractions, the language of employment reframes TOR as a social stabiliser as much as a commercial entity.

Expansion Plans and the Employment Multiplier

Crucially, TOR’s revival is not being presented as a static return to legacy operations. Expansion plans tied to a multi-billion-dollar reset envision deeper processing capacity, improved efficiency, and alignment with West Africa’s evolving product demand. Each layer of expansion widens the employment funnel, from construction-phase labour to long-term technical and managerial roles.

The refinery’s gas-to-power discussions reinforce this trajectory. A shift toward gas-based operations is not merely an energy transition signal; it implies new skill requirements, new maintenance regimes, and new operational interfaces with the power sector. GRIDCo’s engagement with TOR underscores this alignment. Power sector coordination is labour coordination by another name, binding engineers, planners, and system operators into a shared operational ecosystem.

Industry voices have taken note. Downstream players describe TOR’s revival as a strategic boost, not only for supply security but for sector confidence. Confidence, in turn, unlocks hiring, training, and longer-term workforce planning across the downstream value chain.

International Validation, Domestic Consequence

TOR’s re-emergence has also been showcased beyond Ghana’s borders, where it is being positioned as evidence that African refining assets can be rehabilitated rather than abandoned. On the international stage, the refinery’s story is being told as one of industrial recovery anchored in people as much as infrastructure.

That framing matters domestically. International validation strengthens the political space to invest further in skills, expansion, and integration. It also reframes TOR workers not as employees of a troubled parastatal, but as participants in a continental energy narrative.

The Test Ahead

None of this immunises TOR from scrutiny. One would rightly ask whether jobs created today are sustainable tomorrow, whether governance reforms are institutionalised or personality-driven, and whether expansion plans translate into bankable execution. These are fair tests.

But measured against its own recent history, TOR’s trajectory marks a decisive shift. The refinery is once again being discussed in terms of work done, skills deployed, and value retained. For an asset that had become synonymous with idling and internal conflict, that alone represents a structural change.

TOR’s revival, at its core, is a reminder that energy policy ultimately lives or dies where people work. In reclaiming its refinery, Ghana is not just restarting machinery. It is reactivating labour, restoring dignity to industrial work, and reasserting a form of energy sovereignty that shows up every morning in hard hats and overalls.