Ghana Energy Commission Asserts Full Regulatory Grip on EV Charging and Battery Swap Ecosytem

The Energy Commission has convened in Ho to review draft regulations that would license and regulate Ghana’s entire EV charging and battery swap value chain, a pivotal step in formalising oversight of Africa’s fastest growing electric mobility market and anchoring investor confidence in a rapidly expanding sector.

Ho, Volta Region | February 21, 2026 - The Energy Commission has opened a two-day board meeting in Ho to review draft regulations that would formally empower it to license and regulate the entire electric vehicle charging and battery swap value chain, a decisive move toward structuring one of Ghana’s fastest moving energy frontiers.

At stake is not simply rule making. It is jurisdiction. The Draft Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure and Battery Swap Systems Regulation, once passed by Parliament, would give the Commission statutory authority over the manufacturing, assembly, importation, installation and operation of EV charging infrastructure and battery swap systems across the country. In effect, it would consolidate oversight of a sector that is expanding faster than its rulebook.

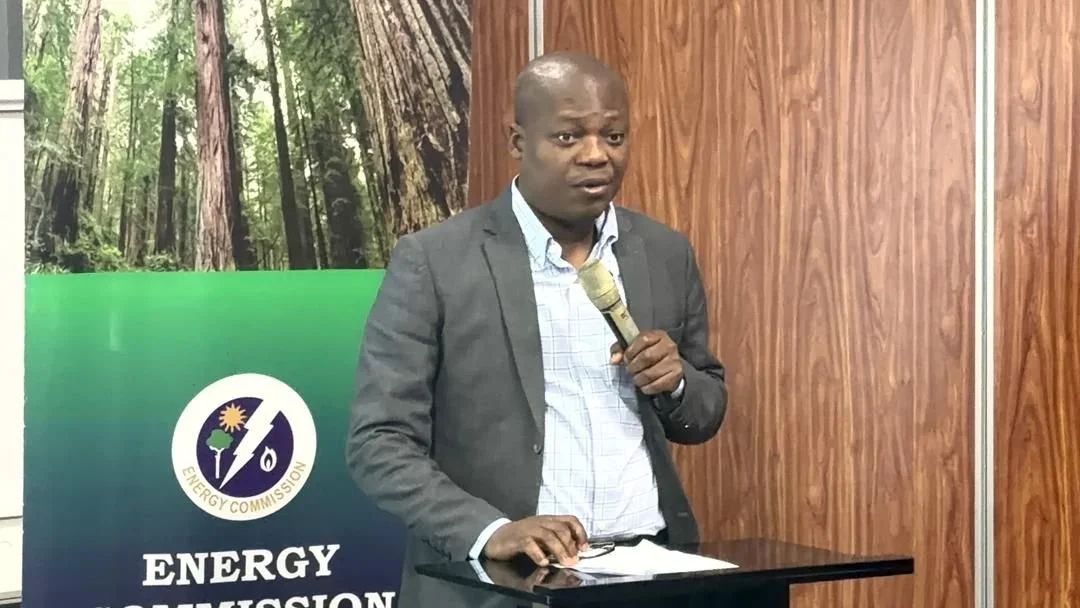

Board Chairman Professor Gartchie Gatsi framed the exercise as foundational. The proposed regulations, he noted, provide the legal basis for regulating what is no longer a peripheral niche but an emerging industrial ecosystem. Structured around four pillars, residential charging, workplace charging, public and commercial charging stations, and safety requirements for charging and battery swap systems, the framework aims to create coherence from garage socket to grid scale deployment.

Ghana enters this regulatory phase with momentum. By the Energy Minister’s count, the country now hosts roughly 17,000 electric vehicles, the highest penetration rate on the continent. That footprint, once anecdotal, is now large enough to demand standards architecture: voltage protocols, installation codes, safety thresholds and licensing discipline.

The Commission’s Deputy Director of Energy Efficiency Regulation, Mr. Kennedy Amankwah, underscored that transparency and public participation have been central to the drafting process. Regional sensitisation exercises have already been conducted across targeted capitals, a nod to the fact that charging infrastructure, unlike thermal plants, sits close to households and commercial corridors.

Ms. Joyce Caitlyn Ocansey, Coordinator of the Drive Electric Programme, sharpened the policy edge. The regulation, she argued, is not merely about infrastructure. It is also defensive industrial policy. Without clear import and technical standards, Ghana risks becoming a terminal market for aging internal combustion fleets displaced from stricter jurisdictions. Properly structured, the framework positions the country to absorb green technologies rather than their obsolescence.

This regulatory turn arrives as foreign interest in Ghana’s domestic EV architecture intensifies. Technical diplomacy between the United Kingdom and Ghana has begun to explore battery localisation and assembly possibilities, while domestic players eye value addition beyond simple vehicle importation. In that context, the absence of a licensing backbone would be more than a legal gap. It would be an investment deterrent.

The Commission’s assertion of authority also aligns with its broader regulatory arc. Recent efforts to tighten port surveillance at Tema Port signal a tougher stance on substandard electrical imports, protecting grid integrity and consumer safety. Parallel initiatives under the Energy Efficiency Revolving Fund and Ghana’s engagement with the UN-backed cooling programme reflect a systematic push toward energy-efficient equipment standards, refrigerant transition and local assembly incentives.

In that light, the EV regulation is less an isolated policy and more a structural extension of a regulator seeking to future proof the grid. Electric mobility introduces new load profiles, distributed demand nodes and safety variables. Licensing charging infrastructure is therefore as much about system planning as it is about transport decarbonisation.

The Ghana Standards Authority has already collaborated with the Commission to develop and publish approved EV charging, vehicle and battery standards. The draft regulation would give those standards enforcement teeth.

Should Parliament approve the instrument, Ghana will have moved from enthusiasm to architecture, from pilot installations to a codified ecosystem. In a continent where EV adoption is often framed as aspirational, Ghana’s strategy appears more deliberate: build the roads, wire the grid, then write the rules that keep both from fraying.

For investors, manufacturers and consumers alike, the message is clear. The age of improvised sockets is closing. A licensed, safety bound and standards anchored EV market is taking shape.